By Phyllis Eckhaus

“A shanty is better than a cheap tenement any day.”

—Jacob Riis, quoted in The Decorated Tenement

Jacob Riis—author of How the Other Half Lives, the powerful 1890 anti-tenement tract—was such an effective propagandist that even today his work obscures the vitality, significance, and beauty of many historic Lower East Side streetscapes and buildings.

Look up “tenement”—which we define here as a multi-family dwelling built for working-class families—and one of the synonyms you will encounter is “slum.” No wonder preserving tenements is such an uphill battle!

Yet this longstanding contempt for tenements is, in general, misguided since it dates to a different time, when these buildings were little regulated, and those few regulations were ineffectual. That contempt can also be malevolent, with roots in anti-immigrant sentiment and class antagonism.

A clear-eyed look at many LES tenements that remain today—those built during a time of housing reform and great competition for tenants—reveals an important and positive story: immigrants transcended the efforts to contain and control them, and transformed a neighborhood to reflect their own culture and upward mobility.

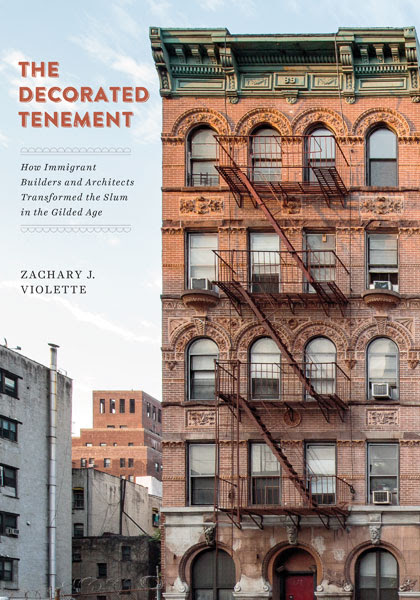

Such tenements have been wrongly condemned, literally and figuratively. As Zachary J. Violette documents in The Decorated Tenement, his ground-breaking study of the ornamented late 19th and early 20th century dwellings on the Lower East Side (his book also examines Boston), these tenements remain special and wonderful, signifiers of immigrant progress and pride.

Among Violette’s findings:

Virulent anti-immigrant feeling plus idealization of the suburbs have prevented pundits from appreciating tenements.

Violette is especially good at exposing the anti-Semitism that fueled the mainstream maligning of tenements, from Riis referring to the presumably Jewish investor-builder seeking his “pound of flesh” to the early 20th century reformers who denounced distinctive ethnic streetscapes, reserving their harshest language for the “riotous crudeness which is typical of Jewish neighborhoods.”

And we who love New York City readily forget the ever-present proselytizing on behalf of the American Dream House: a suburban single-family house with a yard, beloved with a religious fervor. Church leader William B. Patterson put it plainly in 1914: “The tenement is an impediment to God’s plan for the home.”

Decorated tenements embodied cutting edge-innovations, vastly improving the housing available to working people.

Years before reform laws prohibited construction of the airless, crowded, dark tenements rightly condemned by Riis, better tenements were already on the rise, some of them designed by immigrant or ethnic architects highly-trained in Europe. They took pride in upgrading the appearance of tenements with materials suddenly made possible through mass production. The “crude and flamboyant monstrosities of the Jewish builder,” as housing reformers put it—elaborate masks, pilasters, belt courses, cornices, etc.—were enabled by the newly available terra cotta, cast iron, and pressed sheet metal.

Violette notes that by the mid-19th century, “[n]o American city had higher standards for visual culture than New York, increasingly the center of national culture.” The city’s commercial prosperity and flourishing production of architectural materials spurred the construction of “everyday buildings that would have been perceived as elegant elsewhere in America.” Middle-class New Yorkers demanded ornament, and later, working-class LES immigrants did as well, with the tastes of the latter shaped by the elaborate stylings of urban European streetscapes.

Decorated tenements reflected immigrant social mobility.

Violette demolishes the claim, put forth by Riis and others, that decorated tenements were a scam meant to hoodwink immigrant families into renting degraded dwellings. Instead, immigrant families had agency and were constantly on the move looking for the next best thing. Indeed, the competition for tenants was so fierce, and improvements so rapid, that builders were advised that their window of opportunity for making the return on their investment was merely their new building’s first five years. Small-scale builders often lived in their own buildings.

The insides of tenements were also dramatically upgraded to meet tenant demands. Increasingly typical were features that previously seemed beyond reach: kitchens with gas ranges, hot water boilers, electric lighting, sinks with running water, sewer connections, dumbwaiters, flush toilets and full bathrooms, separate parlors, wallpaper, folding blinds, and more. While patronizing patrician critics often dismissed the aesthetics of these interiors—social worker Mabel Kittridge tried and failed to promote ascetic furniture and bare floors—they were what aspiring working-class and immigrant families actually wanted.

Tenements and streetscapes democratized the appearance of the city.

Here Violette is eloquent: “The elaborate street façade of the decorated tenement was one of the great democratizing moments of the period,” with working-class people proudly and defiantly appropriating the styles and signifiers of progress, modernity, and high culture.

Immigrant builders and families dared to take up space and do it their way, creating low-rise buildings and streetscapes of unique historical and cultural significance, as well as immense charm. Zachary Violette compels us to see these sites anew—and to actively appreciate and preserve them before it’s too late.